It is 1862. London is in the midst of expanding 5 times its size into the largest city in the world—rapid expansion has created conditions for slums the size of entire cities. With an ever increasing wealth gap between the rich and poor, writers, philosophers, and artists are driven to work towards commenting, challenging and changing the social conditions that create this dystopia. Charles Dickens writes Great Expectations in serial form from 1860-1861, Ruskin begins publishing his work, “Unto This Last” where he critiques industrial economics and argues labourers should receive a living wage; and what does the artist do? The artist makes wallpaper.

That’s right. Wallpaper.

Wallpaper to change the world.

I love artists so much. We are such an odd little bunch. We look at massive problems like the increasing wage gap and think to ourselves, “what can help this situation?” Weirdos like me learn to thatch roofs, while artists like William Morris designed wallpapers.

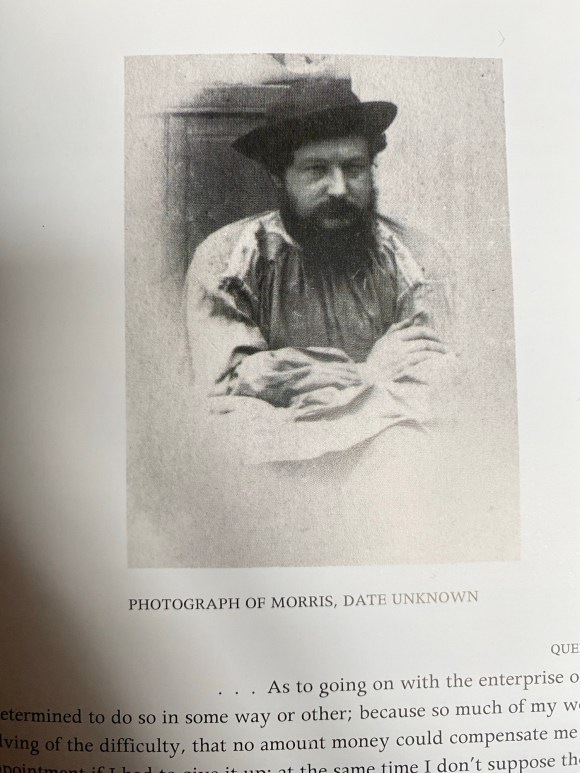

William Morris was a British artist, writer, medievalist and social theorist—among many other things. Born into a well-to-do family in England during a time when pre-union industrialization was at its peak. Morris looked around, and, sensitive to the ways in which his privileged life was at the cost of working class lives, set out to change the social fabric. While he accomplished many achievements in his life, he is now most commonly known for his wallpaper.

While there are many great reasons to love Morris & Co designs, I wanted to highlight three unique things that shed light into why this artist looked around at social inequity and designed wall paper.

Elevation of local nature—Morris printed his first paper, Trellis, one decade after the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace. In this exhibition London positioned itself as a leader of world empires by showcasing all the amazing things the British Empire was making and doing—including wall paper. Popular during this time were designs influenced by French florals and exotic flowers. Morris defied this by depicting common flowers found in English gardens, like roses and daisies.

Beauty should be accessible—in the 1860s wall paper was emerging as a much more accessible option for home décor than the opulent textile based wall hangings. While wallpaper remained elusive to working class families, the ideal behind Morris’s designs and his venture into the field was driven by his socialist ideas: beauty should draw one closer to nature, and be accessible for Victorian households.

Lastly, at a time when the ravages of the industrial revolution were taking a massive toll on labourer’s of all ages—children included—Morris looked back to the time of Medieval guilds as a guide to a worker owned production. While it is common to think of the social inequity of feudalism in medieval Europe, Morris looked at the devastation of the industrialization of labour practices and thought to lift up guild solidarity as a model for what good labour might look like. His vernation of medieval life is apparent in much of his design and illustration work.

Next Sunday, March 24th, will be Morris’ 190th birthday. I for one will be raising a glass to this weirdo artist and his attempts to change the world with wallpaper. I see you, Morris. You have certainly enhanced the life of this off grid weirdo artist.